Growing attention on the risks associated with per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), a group of manufactured chemicals which have been used in industry and consumer products since the 1940s, is creating uncertainty about how to accurately incorporate into environmental due diligence—even as regulations and thresholds are still taking shape. At the Environmental Bankers Association’s summer conference, LightBox senior vice president Alan Agadoni moderated a panel titled “The PFAS Momentum Conundrum” featuring Chuck Neslund, Eurofins Lancaster Laboratories Environment Testing and AEI Consultants’ Victor Detroy for a timely discussion on the growing availability and quality of PFAS due diligence data, successful strategies for assessing PFAS risk, and the latest intel on analytical methods that are quickly gaining traction as current best practice.

Evolving PFAS regulation

Suppose you saw the movie Dark Waters starring Mark Ruffalo. In that case, you know the background behind attorney Robert Billot’s efforts, which began in 1998 to hold DuPont accountable for knowingly contaminating a rural West Virginia town with unregulated PFAS chemicals. Since then, although current scientific research suggests exposure to certain PFAS may lead to adverse health outcomes, studies are still ongoing to determine how different levels of exposure to different PFAS can lead to various health effects. The results of a recent scientific study set the wheels in motion for the U.S. EPA to establish risk exposure thresholds. Still, PFAS are not recognized as hazardous substances under CERCLA. Various states have regulations governing PFAS, but there are not yet any federal drinking water exposure limits.

The momentum conundrum

“The conundrum,” noted Agadoni at the EBA conference, “is that while more information on PFAS risk at commercial properties is positive, we see a lag in the science, standards, measures, and methods. That leaves us with strong momentum regarding awareness and data but a lag in the tools needed to conduct solid engineering and environmental due diligence.“

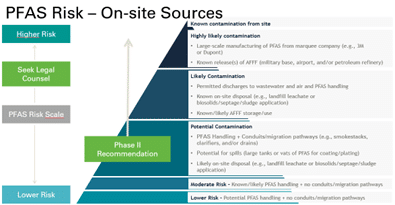

Environmental due diligence consultants are in the difficult position of making decisions with their clients about how to assess PFAS risk, conduct sampling and interpret results while scientists are continuing to conduct and review the growing body of research about PFAS and regulators are exploring how to define exposure limits and how to prioritize regulations for the most hazardous PFAS. Of particular concern are Phase I ESAs conducted at properties involved in activities that are associated with PFAS use and disposal, such as sites where fire extinguishing aqueous film-forming foams (or AFFFs) were used to extinguish flammable liquid-based fires (e.g., airports, shipyards, military bases, firefighting training facilities, chemical plants, etc.), plus manufacturing or chemical production facilities (e.g., metal plating, electronics, certain textile and paper manufacturers, cookware, etc.).

Growing universe of PFAS Due Diligence Data

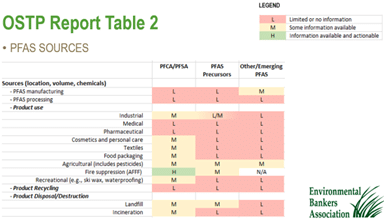

In March 2023, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) released a state-of-science report on PFAS based on comprehensive outreach to various federal agencies. The report, a high-level overview of research on PFAS as a chemical class, contains a complete agency-by-agency compendium of scientific research efforts to address PFAS risk. This document’s critical role is laying out the current body of knowledge which will ultimately shape policy decisions. Over the next year, OSTP will work with federal agencies to “leverage this report as a roadmap for establishing goals and priorities for federal PFAS R&D, harness existing federal PFAS research activities, and accelerate transformative advancements in the destruction and disposal of PFAS, the development of PFAS alternatives, and in our understanding of the harmful effects of PFAS as a chemical class on human health and our environment.” Thus, it is an essential resource for environmental professionals who must stay abreast of the latest PFAS research to advise their clients adequately.

Table 2 of the OSTP Report includes a valuable table which delineates the available data level (limited/no, some information or information available and actionable) for specific types of sites associated with PFAS risk. For instance, as shown in the accompanying table, the report identifies the use of AFFF as one use with “information available and actionable.” Other uses denoted in pink in the table are data gaps with only limited or no PFAS information available. This research notes the start of reflection by the federal government to catch up with where the states that took an early lead on PFAS regulation are today.

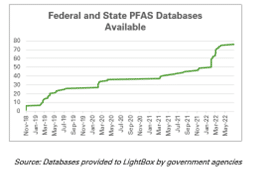

Since 2018, the number of PFAS databases provided to LightBox by federal and state government agencies has been increasing at a compound annual growth rate of more than 100% each year. “The range of property data related to PFAS is expanding rapidly and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. We have an obligation to separate the noise from the data and information that shapes how we do things like environmental due diligence based on the best available information,” observed Agadoni.

Successful strategies for assessing PFAS risk

Now that readily available and reasonably ascertainable property records address PFAS risk, environmental professionals are developing best practices for incorporating PFAS considerations in their Phase I ESA process. Detroy outlined a general approach AEI Consultants uses to assess PFAS risk in Phase I ESAs, starting with initial screening for PFAS using the recently released EPA PFAS Analytic Tool, state screening tools and databases, and industry sector and NAICS code review. After that, if warranted, “we essentially look at standard ASTM E1527 historical data sources through a PFAS lens,” especially if the target property is an airport or involves operations associated with high PFAS risk. Research may progress to a site inspection or consider other factors, like nearby drinking water wells, to assess PFAS risk. Ultimately, Detroy shared, “It comes down to: ‘What’s the risk associated with PFAS at this property?’ There are many unknowns, but we have enough information to characterize risk into categories and make sampling decisions based on what we learn about a property in our standard research.”

Important considerations on PFAS testing and analytical methods

If a Phase I ESA identifies a potential PFAS risk, the challenge becomes defining the scope of testing and the approach to be used. “When you need to have PFAS testing done,” Neslund advised, “you need to ask: ‘What are the testing results to be used for? Is it drinking water compliance? Wastewater? And then make sure the methods being used are appropriate. Decisions about how to test, how to use the test data and how to interpret the data are where the confusion comes in.”

Without a USEPA standard method for PFAS in anything other than drinking water, there have been questions about the validity or comparability of user-defined methods for the past several years. Neslund encouraged the audience to get familiar with the EPA draft method 1633, a targeted analysis for 40 PFAS compounds lenders and environmental professionals can rely on specifically on investigations of drinking water, solids, biosolids and landfill leachate.

The approach “fundamentally aligns with the user-defined methods which have been the basis for PFAS testing for the last two decades,” Neslund said, “so we expect a certain degree of comparability in the data sets as we transition from one method to the other.” This method is currently undergoing a multi-lab validation effort as part of the rule-making process. There has been somewhat of a fractured response to the utilization of this method so far, but states are paying attention. New York just transitioned to using the draft method regardless of certification status.

For more information